THE FAIREST FORCE

1. BEFORE THE WAR

*****

Miss Campbell Norman and QAIMNS nurses, Royal Victoria Hospital, Netley, 1891

*****

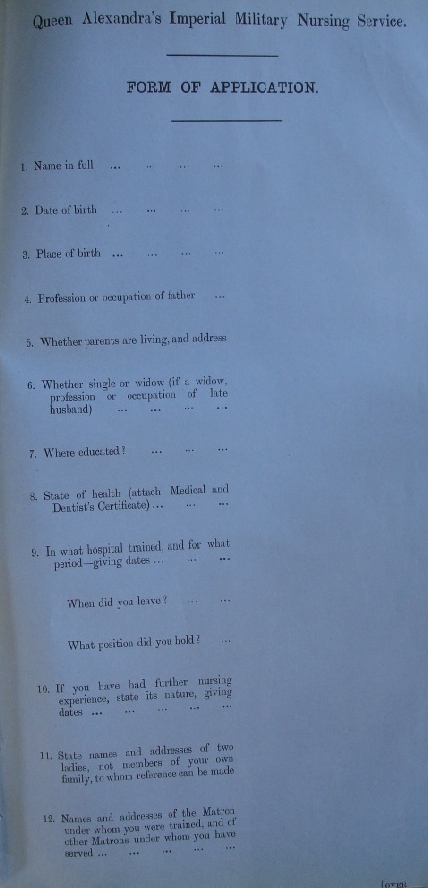

The original application for for admission to QAIMNS which continued relatively unchanged through the Great War, and always in blue (The National Archives WO243/20 and to be found in a large proportion of nurses' service records)

For admission to the Service, women had to be between twenty-five and thirty-five years of age, single or widowed, well-educated, and of good social standing. On paper, widows had always been acceptable, but there is no case of one actually being employed between 1902 and the outbreak of the Great War in 1914. A full three year nurse training was a necessity, undertaken in a hospital approved by the QAIMNS Nursing Board.[6] This last requirement caused considerable problems as the 'approved list' consisted of only thirty-four hospitals throughout the United Kingdom, all large teaching hospitals, and therefore excluded the vast majority of trained nurses. At a meeting of the Nursing Board on 15 June 1904, Sydney Holland, the Chairman, drew attention to the fact that:

'… desirable candidates were sometimes lost to the service owing to their not having been trained at hospitals of 100 beds and over … that nurses may, in some cases, obtain a more thoroughly practical training in small hospitals than in large ones with Medical Schools attached. In the latter class much nursing work is carried out by students, whereas in small hospitals all the nursing and the dressings, as well as the sterilization of instruments and appliances, are done entirely by the Sisters and Nurses, who obtain thereby a familiarity with details of their profession which is not possible in those large hospitals which educate students for the medical profession'.[7]

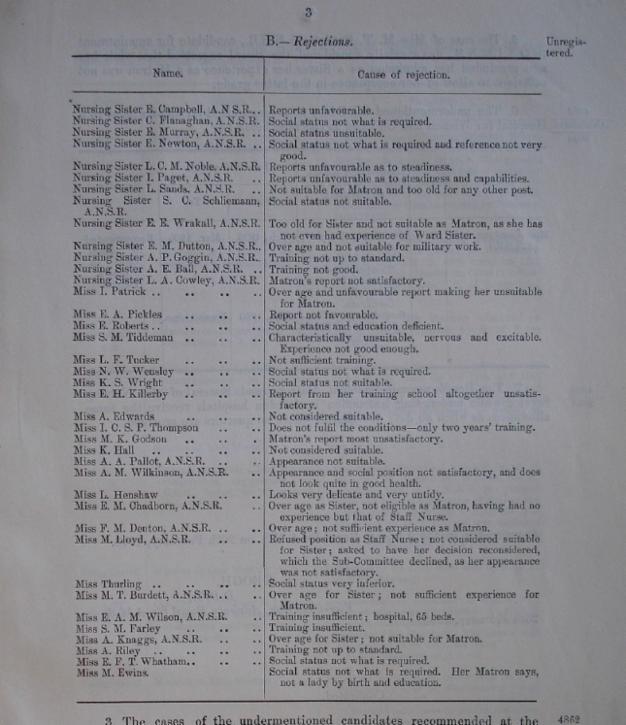

He urged the Nursing Board to consider applications on their merits, and in spite of an initial reluctance, soon a number of nurses were being appointed from smaller hospitals and Poor Law infirmaries nationwide, though with the majority still coming from those hospitals with medical schools attached and particularly from the capital. Despite this one concession, the insistence on women having good social connections was not relaxed, the application form asking for the names of 'two persons to whom reference can be made, one being a lady, not a member of your own family'. Some forms had the wording altered by hand to request that both referees should be 'ladies,' but as the years passed more emphasis was placed on references from matrons of the applicants’ training hospitals, with only one reference required to confirm their social suitability. During 1903 and 1904 the minute books of the Nursing Board demonstrate that while there was difficulty in recruiting sufficient nurses to fill available posts, there was certainly no lack of applicants.[8] However, the majority failed either to provide a sufficiently good hospital reference, or more likely failed to impress the interviewing panel, the reason for their unsuitability being spelled out in the minutes of the meeting in plain terms. Miss W. P. was merely 'too delicate for the work; could not go abroad', while Miss L. D. had 'an apparent want of social standing, and appearance unsuitable'. Even worse, Miss W. was rejected on the grounds that she was a 'coloured lady from America', Miss N. H. was 'flippant' and Miss M. M. 'Quite unsuitable. Father was an iron-plate worker; mother cannot sign her name'. These comments continued for two years, until in June 1904 it was decided that any future observations as to social status should be omitted, and replaced by less descriptive comments such as 'not considered suitable' or 'not recommended.'[8]

One of the very long lists of women rejected as unsuitable for QAIMNS during the early days of the service. Some later went on to serve with QAIMNS Reserve during the Great War (The National Archives WO243/20, 11 February 1903)

‘When a young woman of 28 has finished her training at a civil hospital, she looks around and decides what her future is to be ... If she stays in her civil hospital, promotion is rapid. But in the military service the promotion will be, and always has been, very slow. In civil work there are many openings for obtaining a better position and salary, in military nursing, very few. Another reason why promotion must be slow in military nursing is that once having been in it for any length of time, a nurse, never mind what her position, is absolutely debarred from any nursing appointment outside the Service. No matron of a civil hospital would take in to her hospital a nurse who has been in a military hospital, a nurse who has had no experience in the nursing of women and children or of old people... The result is that ‘once in, always in’ must be the state of affairs for any woman taking up military nursing. To sum up, if a nurse stays, she unquestionably loses her nursing pecuniary value. Her capital, so to speak, is depreciated.’ [10]

These recommendations resulted in improved pay and increased benefits on retirement, or in cases of resignation on medical grounds. The maximum attainable pay for the most junior of grades, the Staff Nurse, rose from £35 to £40 per annum, and for a senior Matron, went up from £120 to £150 per annum, thus bringing pay into line with that of the larger civil hospitals. This scale remained unchanged throughout the following ten years, still being in force at the outbreak of the Great War.

During the peace that existed between 1902 and 1914 life for members of QAIMNS was cultured and respectable, both on and off-duty. Their working hours may have been long, but their duties were usually far from onerous, with much of the day to day ward work being undertaken by orderlies of the Royal Army Medical Corps. They made beds, supervised the washing of helpless patients, carried out wound dressings, ensured that meals were properly served, and gave out medicines at the appropriate time. However, during peacetime men were very often suffering from minor illnesses and fevers or from the result of accidents, and few were bed-bound or in need of intensive round-the-clock nursing care. The teaching of RAMC nursing orderlies was considered an important part of nurses’ work, although at the same time the sisters had no control over orderlies’ working hours or time off, nor the power to reprimand them. In an attempt to clarify the chain of command, in 1903 Standing Orders for QAIMNS and the RAMC stated that:

[orderlies]… will in hospitals when working under sisters and staff nurses, give prompt obedience to all instructions given to them … as regards medical and sanitary matters and work in connection with the sick, the matrons, sisters and staff nurses are to be regarded as having authority in and about military hospitals next after the officers of the Royal Army Medical Corps, and are at all times to be obeyed accordingly, and to receive the respect due to their position.[11]

During this period of peace there were more than 300 British military hospitals in the United Kingdom and overseas. Among the home hospitals only ten provided more than 200 beds, and the majority were small barrack hospitals with a few beds set aside for short-term sick soldiers from local regiments. Ninety of these hospitals had less than ten beds, some were obsolete. Conditions were frequently poor, and graphically described in a series of inspection reports compiled in 1903. At Preston Barracks, Lancashire:

We found this hospital in a disgusting condition of dirt and neglect. The dispensary floor was covered with litter, the drawers full of rubbish; the bread crocks not lately emptied; old newspapers between the bedding; the larder extremely dirty. It is, in fact, difficult to understand how this condition of things, evidently inveterate, could have escaped the notice of those in authority.

While nearby Burnley:

... Was in a most deplorable condition of filth and neglect, and was quite unfit for habitation. The non-commissioned officer in charge was, at the time of our visit, under arrest, and the equipment was removed. If this hospital is ever to be reopened, much will require to be done to make it suitable for sick soldiers. In fact the whole barracks presented a picture of the most abject squalor, and the sight of them must have a strongly deterrent effect upon any man in Burnley who might think of enlisting. [12]

In an effort to improve nursing care within the Army, from 1903 trained nurses of Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service were employed in all military hospitals with more than one hundred beds both in the United Kingdom and also overseas in Malta, Gibraltar, Egypt, South Africa and Hong Kong. There were many opponents to these arrangements within the ranks of the officers and men of the Royal Army Medical Corps who felt that the introduction of women into a previously all-male environment was not only unnecessary, but also detrimental to the provision of care and good order in military hospitals. Nurses needed to tread carefully in negotiating the minefield of Army doctors, Wardmasters, NCOs, orderlies and patients, and trying to meet the expectations of many different groups while retaining both their personal standards and professional autonomy. In appointing women to the service who were both well-educated and from middle-class backgrounds, the Nursing Board had chosen well. It ensured that nurses had the social skills to mix with both senior doctors and sick officers, while retaining a ‘lady and servant’ relationship with their other patients, thus ensuring that the latter were unlikely to take advantage of the fact that they were being cared for by women.

Both the medical and nursing staff of military hospitals were small during peacetime, but there was a clear understanding that the likelihood of war was ever present. In the early years of the twentieth century, following the war in South Africa, committees were set up to develop plans for the expansion of hospitals in case of war with regard to all medical and nursing staff. With the benefit of hindsight these plans fell far short of what was actually needed in the event, but at that time the extent and duration of another conflict could not have been foreseen.

*****

A fuller portrait of the background of members of the pre-war 'regular' branch of Queen Alexandra's Imperial Military Nursing Service can be found in this article:

on the 'Background Extras' page

*****

[5] The National Archives, WO25/3956

[6] Regulations for Admission to the Queen Alexandra Imperial Military Nursing Service, 1902, The National Archives WO32/6404

[7] The National Archives, WO243/22, page 68: The Nursing Board, QAIMNS, Proceedings and Reports

[8] The Nursing Board, Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service, Proceedings and Reports, The National Archives, WO243/20 to WO243/28

[9] Ibid. WO243/21

[10] The National Archives WO243/21, page 69

[11] Standing Orders for QAIMNS and RAMC, November 1903, cited in ‘Angels and Citizens,’ Anne Summers, Routledge and Kegan Paul Ltd., 1988

[12] The National Archives, WO30/143 Advisory Board for Medical Services; Inspections without Notice of Military Hospitals