THE FAIREST FORCE

7. UNIFORM

*****

*****

Although the common perception today of Great War military nurses is one of women in similar grey-tone clothes, there were many differences in uniform that marked them out both by service and seniority and it was colour that could highlight their presence at a distance. In a world of khaki, a Medical Officer might be guided by a flash of red across a tented field which marked the position of the Sister-in-Charge of a Casualty Clearing Station, while a sick or wounded soldier could make no mistake about his surroundings when he opened his eyes to the soft greys and blues of nurses’ dresses.

The regulation uniform of Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service had been virtually unchanged since 1881 and if their grey dresses were of a similar style to those worn in many civil hospitals, the red shoulder cape or ‘tippet’ was a unique feature that clearly identified them as part of the British Army. In 1904 it was decided that the solid red cape should be confined to the permanent staff of QAIMNS with members of the Army Nursing Service Reserve wearing a similar style in grey serge with a scarlet border, a pattern that then continued through more than five decades.[72] When the Territorial Force Nursing Service was formed in 1908 their uniform followed the same style with minor changes to the cape which was described as ‘blue-grey’ but with the same scarlet border.[73] In peacetime these differences might be obvious but in wartime they became blurred when with washing, wearing, repairing and a shortage of material, capes of the QAIMNS Reserve and the TFNS began to look very similar indeed.

Seniority in the service was marked in a number of ways. For work, all nurses below the rank of Matron wore similar mid-grey cotton dresses. Sleeves on the dresses of staff nurses were plain, with nursing sisters being marked by the addition of two scarlet bands, one inch wide, above white cuffs. Matrons wore grey serge dresses rather than the ‘washing’ cotton of the other members, with scarlet cuffs to their dresses but no sisters’ stripes. Assistant Matrons were sometimes seen with white cuffs and three scarlet stripes on their sleeves but as many Assistant Matrons were, in wartime, actually substantive sisters ‘acting’ in a higher rank, the fine detail and accuracy of uniform can become confused. All grades wore the familiar white muslin caps flowing down and outwards from the headband in a fashion that became known as ‘Army style.’

Before the war, bonnets and cloaks were provided for outdoor wear but the Great War raised the need for more practical outerwear in the form of mackintoshes and woollen cardigans. The latter were never ‘regulation’ but universally worn in cold climates, both over and under shoulder capes. It was far from high fashion but a necessity for survival in active service conditions in winter and one to which the authorities turned a blind eye.

Matron Ethel Minns, No.2 General Hospital, Le Havre, wearing a woollen cardigan under her uniform cape

In 1915, bonnets fastened with ribbons under the chin were phased out, Panama hats permitted for summer wear, and from 1917 ‘storm caps’ were increasingly seen especially in France and Flanders where wind and rain were always an enemy.

… the Matron-in-Chief [at the War Office] informed me that a small close-fitting cap had been authorised but these were only to be worn in camp or on board ship in windy weather and on no other occasions. Also received letter from the Commandant-in-Chief, V.A.D.’s, saying that velour hats were not sanctioned for members of the V.A.D.[74]

Uniform regulations for QAIMNS issued in 1916 remained virtually unchanged from former times and although listed both summer and winter cloaks they did not include any form of serviceable coat. However, photographs of the time show that both overcoats and mackintoshes had indeed become standard issue, at least in France and Flanders, though styles varied.

Conditions in hospital camps and casualty clearing stations ensured that hemlines which started the war three inches above the ground rose substantially over the next four years to a point well above both the ankles and the mud. Members of each of the three services, QAIMNS, its Reserve and the Territorial Force Nursing Service wore individual service badges on the right lapel of their tippet and today these badges can provide the most reliable way of distinguishing between them in photographs. In addition, members of the TFNS displayed silver badges in the shape of the letter ‘T’ on the points of each lapel of the tippet.

Members of both services were given an annual allowance of £8.00 a year while serving at home, or £9.00 when overseas to provide themselves with appropriate uniform and maintain it in good condition. During wartime, with so many women joining and leaving within relatively short periods, uniform was passed on and altered where necessary, saving both on scarce materials and also proving a financial advantage.

Female members of Voluntary Aid Detachments were issued with uniform of a completely different style to that of the trained nurse. Strict dress regulations were set out by the Joint War Committee for both indoor and outdoor wear and from 1915 the uniform received protection under the Defence of the Realm Act.[75] In 1916 the British Journal of Nursing reported:

Members are again emphatically reminded of the necessity of conforming to the details of uniform laid down in Regulations, and that they should take pride in keeping their uniforms clean and tidy. The V.A.D. uniform is registered under the Defence of the Realm Act, and must not be worn except for work on behalf of the sick and wounded. It is hoped that the issue of a Joint Certificate of uniform will prevent the illegal use of the registered uniform, and also the wearing of uniform by members who have resigned or left their Detachments. [76]

For those VADs of the British Red Cross Society engaged in nursing duties, working dresses were of light blue cotton and for those of the St. John Ambulance Brigade, the same style in mid-grey. Brassards were worn on the upper arm and displayed either a red cross or the eight-pointed star of St. John. Although aprons should have shown similar symbols, the privations of wartime soon ensured that many aprons were white with no distinguishing features.[77] Special Military Probationers were women with little or no previous nurse training employed on identical terms to VADs but under contract to the War Office and with no affiliation to the Joint War Committee. Their uniforms were similar in most respects to those of British Red Cross Society VAD but without the badges and insignia and with plain aprons. For both groups, aprons were designed to offer practical protection rather than high fashion, with high round-necked bibs tucked under the collar, and long enough to cover the dress. Shoulder straps crossed over at the back and fastened with buttons at the waistband.

Pre-war, female members of Voluntary Aid Detachments wore small plain white caps of the ‘Sister Dora’ style which remained the most common and iconic form of nurses’ headwear in civil hospital for many decades afterwards. As the number of hospitals grew in the UK, some auxiliary hospitals decided that their VAD staff would look more professional and attractive if they adopted the ‘Army style’ veil, a step which found disfavour among trained military nurses nationwide. The wearing of hats this way by VADs was also evident in France where the Matron-in-Chief reported:

Found some of the VADs with Army caps on at Etaples, and was informed they were permitted to wear them. Instructed them to wear Sister Dora cap until I gave them other instructions and wrote to the Matron-in-Chief on the subject on 23rd inst.[78]

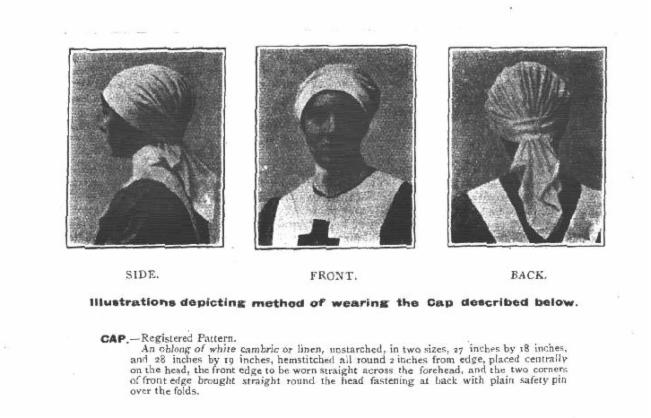

It was about this time in the autumn of 1915 that the style of the VAD cap was officially changed by order of the Joint War Committee. The Sister Dora hat was phased out over the summer months and substituted with a style that later became an iconic mark of the Great War VAD. The new head-dress was more complicated to arrange correctly than its predecessors, and although it has become a common-place sight to us today, was greeted in an entirely different manner then. Dorothea Crewdson had her first meeting with a new hat in November 1915:

C is singing at a concert tonight, very much alarmed in case she should have to wear the new cap. We are all sporting them now, not the St. John people who have had no orders, but Red Crosses all have them. They are oblong instead of square like the Sisters’ and worn pinned over at the back instead of under. Rind got the caps from England. Matron saw them in the evening and gave orders we were all to wear them next day, so at breakfast we all hurried in rather self-conscious and latecomers, who had more of an audience, were greeted with shrieks of laughter and remarks of numerous critics. Altogether the new caps caused great commotion and flutter but as all these excitements soon do die down, no one will think any more about it.[79]

VADs were expected to buy their uniform from an authorised supplier or make their own to official patterns which were supplied on request. After an initial probationary period of four weeks, women received a uniform allowance of £2.10s every six months although this was usually insufficient to cover the multitude of items, both indoor and outdoor, deemed necessary. Footwear, the most vital of necessities, was not taken into account and must have been a considerable additional expense. Nurses were advised that civilian clothes would not be required while overseas and uniform was to be worn at all times, both on and off-duty. Some items, such as the ubiquitous long woollen cardigan, became acceptable, but action was taken against anyone found sporting ‘mufti’[80] or fanciful clothes in public. In January 1917, one VAD was seen by her superior dining in a hotel in Rouen incorrectly dressed, the situation made worse by the fact that she was also smoking and in the company of two male officers. Her eventual punishment was the choice between resignation and dismissal, a severe penalty for a moment’s pleasure.

Letter received from Miss Crowdy, reporting that she had seen Mrs. L__, VAD, not dressed in proper uniform, and dining out with another VAD and 2 officers, and behaving in a very unladylike manner. She had a pale pink blouse and collarette of pearls and went out into the street smoking. Her behaviour was such that Colonel Stewart and Colonel Pasteur, who were dining with Miss Crowdy, would not allow her to go and ask the ladies who they were.[81]

Photographs of VADs taken during the Great War show a large variety of collar styles being worn with indoor uniform. Regulations laid down by the Joint War Committee were quite specific about what constituted a uniform collar for service in military hospitals which were to be ‘Stiff white stand-up, shaped linen collar of the improved Sister Victoria pattern, fastened by a white stud, to be worn by all ranks.’ And for service in hot climates such as the Mediterranean or Egypt, ‘Plain white muslin may be substituted for the stiff linen ones.’[82] Sister Victoria collars remained the most prominent in military hospitals under War Office control for both trained and untrained nursing staff, but in auxiliary hospitals women increasingly adopted softer collars and over the course of the war they became seen more frequently, especially in summer.

VADs are commonly seen wearing what were known as ‘sleeves.’ These were detachable pieces of white linen used to protect the sleeves and cuffs of ward dresses from becoming soiled during the course of the working day. The uniform regulations describe them as, ‘Of white linen, 15 inches long, same shape as lower part of costume sleeve, fastening at cuff with one button, and with elastic at elbow.’ They were removed at the end of a shift and were not authorised to be worn when off-duty or under outdoor uniform.[83]

From January 1918, in common with other military personnel, nurses were allowed to wear Overseas Service Chevrons on the right forearm of their dresses to indicate the number of years they had served outside of the United Kingdom.[82A] For those whose overseas service commenced prior to the 31st December 1914, the first chevron was red, and all subsequent ones in blue. In practice, few photos seem to show these chevrons being worn. This was partly due to the majority of nurses having ‘home’ service only, but also possibly because women had so many work dresses that the sewing of chevrons would have been a large and ongoing task that was quickly destroyed by the process of laundering.

Matron-in-Chief Maud McCarthy with a full set of overseas chevrons visible on her right arm [IWM Q7991]

In an age when many women were good seamstresses, and making clothes rather than buying them was normal, there were often small and unintentional differences in style and a tendency for some women to adapt their working clothes to make them appear more fashionable. However, throughout a period of five years few real changes were evident and the majority of nurses ended the war in a uniform remarkably similar to that worn in the autumn of 1914.

Many more explanatory photos can be found on the Scarletfinders website, where there are pages devoted to uniform, both for the trained nurse and the VAD

IDENTIFYING UNIFORM - TRAINED NURSES

*****

[72] The National Archives, WO32/6405

[73] Standing Orders for the Territorial Force Nursing Service, 1912

[74]The War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, France and Flanders; The National Archives, WO95/3990, 2 November, 1918

[75] Defence of the Realm Act: Prohibition against unauthorised use of naval, military and police uniforms, decorations, medals and badges; July28th, 1915, clause 41.

[76] The British Journal of Nursing, 22 July 1916, page 67

[77] V.A.D. Department Equipment List; British Red Cross Society 11, 2/62, accessed via Imperial War Museum Women’s Work Collection.

[78] War Diary of Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3988, 27 October 1915

[79] Dorothea’s War, op. cit. page 69

[80] Civilian clothes in someone who usually wears a uniform

[81] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, TNA WO95/3989, 4th January 1917

[82] V.A.D. Department, British Red Cross Society and Order of St. John, Equipment list for V.A.D. Members, 22/11/16; Imperial War Museum Women’s Work Collection, BRCS1/2/62

[82A] Army Order 4 of 1918, published December 1917

[83] Ibid.