THE FAIREST FORCE

12. KEEPING CLEAN

*****

Trying to maintain standards of personal hygiene while on active service abroad was often difficult. During a war that covered more than four years and with medical units in so many different locations, a myriad of different arrangements were put in place in an attempt to provide suitable facilities for women. The Camp Kit issued to each woman before embarkation included a canvas wash-stand and waterproof bucket which gave at least basic access to washing facilities and in some areas, particularly early in the war, these were in daily use. In tented units hot water was usually delivered to living accommodation each morning by male orderlies but tended to be skimpy in quantity and never at an optimum temperature, especially in winter. One VAD, reflecting later on what was important during wartime, was not a supporter of camp-kit washing:

Those canvas baths, for instance, what a bore they've been and how little use except when you had lots of hot water and a batman to empty them - which we had about twice. Do you remember how Jones always spilled hers over everything? And those candle-lamps we were made to get. No use, except to drop grease all over the place. In every camp I went to they were strictly barred after one trial.[133]

Despite the waterproof qualities attributed to them, basins and buckets tended not to live up to their name. It became common practice for nurses in France to buy enamel washing bowls and jugs in local towns which held their hot water in a safer and more useful manner:

To get back to the shopping. The canvas basins and pails in our camp kit have not proved very satisfactory, so we bought enamel jugs (such long ones) and basins. These were handed over to us without any paper – so we went on and carried the rest of our purchases home in our jugs.[134]

Canadian Nurses in tent showing folding canvas washstand with enamel jug and bowl and Beatrice oil stove underneath [Library & Archives of Canada, photos of Alice Isaacson]

Monsieur Le Directeur has made us a great offer – we may use the lunatics’ bathroom twice a week, for one hour, which means four of us bathing at one time, as there are four baths in one room. I don’t fancy bathing in company, but as I have not sat in water deeper than an inch since last year, the temptation is great. I think four of us will try it tomorrow and see what can be done in the way of screens.[135]

And the following day she continued:

Three of us went to another part of the asylum at 7 a.m., and had a deep BATH! Up to our necks in water – glorious! A dear old nun came trotting in when I was in my bath and felt to see if the water was the right heat. She thought the bath was too full and pulled the plug by a patent in the floor. I was sitting on the hole where the water runs away and was sucked hard into it![136]

As the war progressed, many of the large hutted and tented hospital camps provided specially built shower and bath blocks for nurses’ use. Even then, this may only have been one hut with four or six baths for more than one hundred women. During the latter part of the war facilities could still be in short supply and when the Matron-in-Chief inspected No.10 Stationary Hospital, St. Omer, in November 1917, she found:

… although there were two splendid baths, these were useless as there were no arrangements for hot water other than members of the nursing staff carrying large buckets of hot water through the garden, up the stairs and along a huge corridor.[137]

A typical bath block erected in British Camps by the Royal Engineers [IWM Q29188]

The want of a hot bath was much felt, and each evening, along the balcony, heading for the shed on the pier, could be seen a procession of maidens carrying a hot water bottle in one arm and a large jug of hot water in the other hand. To lookers-on from the ships moored beside us, this nightly procession caused much speculation and amusement until one day their curiosity got the better of them and they enquired the meaning.[138]

Things that were difficult for nurses with a firm base were even more so for those working on ambulance trains. Nursing sisters on trains were frequently in a position where even undressing might prove difficult for forty-eight hours or more, and finding anything more than a small bowl of washing water was usually impossible. Starting in October 1914, a series of eleven rest clubs for nurses were established and funded by Her Royal Highness Princess Victoria and there was an additional large club in Boulogne run by Mrs. Robertson-Eustace . These rest clubs had facilities for reading, writing, refreshments and relaxation, with some also providing bedrooms for overnight stays. The clubs could be used by the staff of ambulance trains and barges both for resting when between trips and also for bathing and arranging personal laundry. In addition to the clubs, private houses were rented for the use of the travelling staff in or near base towns such as Rouen and Calais. Even then it was not always possible to provide facilities approaching standards that would have been normal in British households:

Left for Calais after lunch to look for a house near where trains are garaged for the convenience of the Sisters of the trains, where they could have a bath and other necessary conveniences. Arranged with a French woman, who had a nice little house quite close, and who was willing to provide the necessary accommodation, and was willing to arrange to give them hot baths at the cost of 50 centimes each, if a bath can be arranged to put in a nice wash house she has in her garden.[140]

There is no follow-up entry to say whether the house proved suitable, but it was only arrangements such as this that enabled women on active service to maintain a small but essential component of their former lives.

The civilian population in areas occupied by British troops could earn money in various ways, and in addition to renting out bath-houses for a small fee, taking in laundry was an excellent way for French women to increase their income in difficult times. Many of the larger base hospitals had army laundries on the premises or nearby, but many nurses preferred that the washing of their personal garments and underwear remained a private business. As the nursing staff of No.21 Casualty Clearing Station discovered, there was risk attached to surrendering your dirty washing to the army.

Received from DMS 4th Army, a copy of the proceedings of a Board of Enquiry met to investigate and report on the circumstances under which a motor lorry, conveying laundry to 21 CCS had caught fire, and in which personal clothing belonging to the nursing staff had been burned. Forwarded to all the Sisters concerned indemnification claim to be filled in and returned to this office, so that the signature of the OC, 21 CCS, might be obtained. The late nursing staff of 21 CCS is now dispersed.[141]

British Army laundry at St. Omer, staffed by French civilians [IWM Q29567]

In situations where so little kit and clothing were carried, losses such as these could have unpleasant consequences which were not easily resolved and the alternative of paying a small charge to a local ‘laveuse’ was an attractive option.

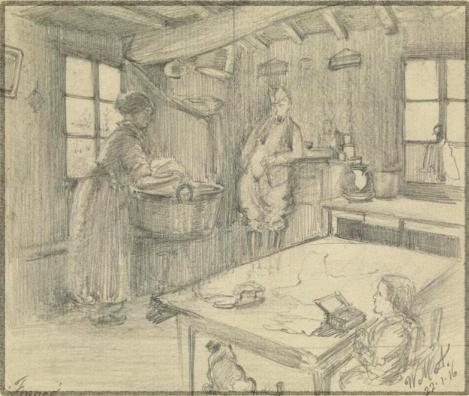

French Farmhouse Kitchen by William Anderson, showing 'Laveuse' [IWM ART16250]

Women who served as nursing sisters and VADs in France during the Great War were drawn predominantly from the middle-classes and had been raised in comfortable, if not always luxurious surroundings. It is certainly a credit to their adaptability and flexibility that they managed to cope with such difficulties surrounding their personal hygiene, often during several years of active service, with so few comments and complaints.

*****

[132] War diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3990, 14 September, 1917

[133] The Importance of a Length of Cretonne, Daily Sketch, 14 April 1919

[134] ‘… in all those lines …’ The diary of Sister Elsie Tranter, 1916-1919; Jennifer Gillings and Julienne Richards, 2008, page 48.

[135] A Nurse at the Front, The First World War Diaries of Sister Edith Appleton, p.28; edited by Ruth Cowen; Simon and Schuster 2012

[136] Ibid., p.29

[137] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3990, 30 November 1917

[138] The Goodbye Book of the Quai D’Escale; IWM, BRC25 0/2

[139] Born Marjorie Edith Leith, married Charles Legge Robertson-Eustace 23/6/1906 and widowed 4/10/1908.

[140] War diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3988, 2 September, 1915

[141] War diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3989, 12 April 1917