THE FAIREST FORCE

13. ON LEAVE

*****

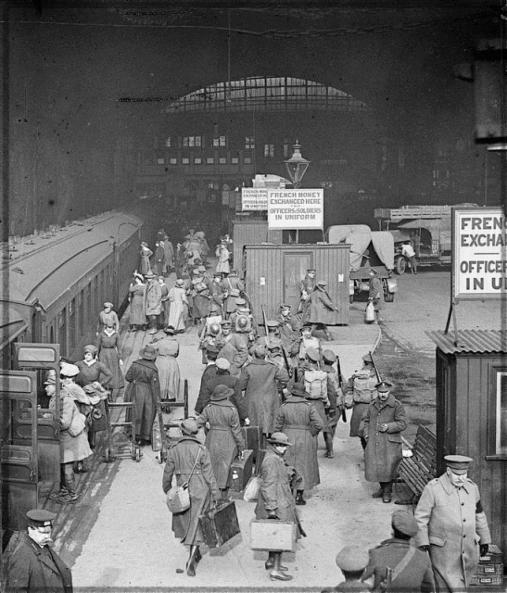

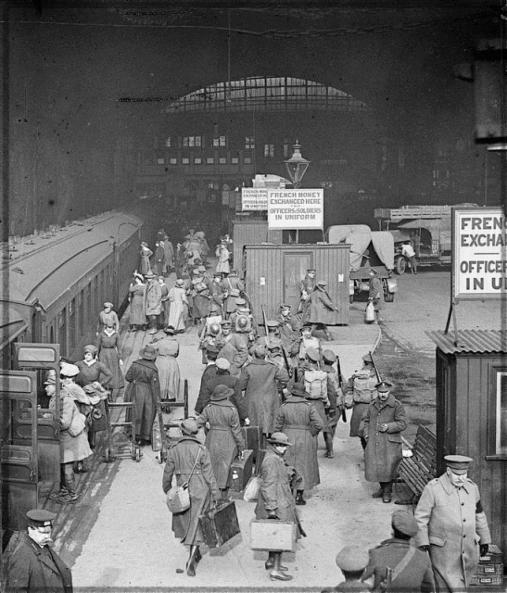

The Leave Train, Victoria Station, London [IWM Q25796]

The Leave Train, Victoria Station, London [IWM Q25796]

As with most other occupations, periods of leave or holiday were part of the contract of employment for both trained and untrained nurses working under the authority of the War Office. The total amount allocated was as follows for each financial year:[142]

Matron 6 weeks

Nursing Sister 5 weeks

Staff Nurse 4 weeks

VAD/Assistant Nurse 4 weeks

In peacetime taking long periods of leave was not always practical when working in overseas stations such as Egypt, Hong Kong or South Africa. It could be accumulated and taken on return to the United Kingdom at the end of the posting, or payment granted in lieu of leave which had been set aside for a period of up to three years. Although France was very much closer, with only the English Channel to negotiate, wartime conditions made the taking of leave no easier. Many more women had to be considered as compared to peacetime. The uncertainty of busy and quiet periods within each individual hospital made staffing needs hard to predict and the overall military situation had a significant effect on hospital staffing. When a military ‘push’ was planned or anticipated all leave would be stopped for medical and nursing staff as well as for soldiers. If the offensive was prolonged it might mean that any leave schedule had to be scrapped and the backlog of those overdue lengthened considerably. The result was that for many nurses thoughts of a brief return to their families and friends in the United Kingdom could be delayed for weeks or months.

In June 1916, with the prospect of a major offensive looming, there was already a great shortage of trained nurses and the cessation of leave was one of the only options left to prevent a breakdown of the nursing service:

He [Colonel Morgan, GHQ] said he had already applied officially for the Nurses, but he doubted whether we should get them. Well, if they don’t come, one must just carry on, but one can’t do impossibilities, and these people who work so hard, I am so sorry for them. However, they will not fail us I am sure, and leave will have to be stopped till more help comes.[143]

Although Miss McCarthy might not have been privy to the details of military operations, the order to stop routine leave for her nursing staff must surely have been an indication of hard work to come, in July 1917:

Circular sent to all Bases notifying that all ordinary leave for nursing sisters should be stopped for the present – applications should be submitted later. Leave under special circumstances will still be granted.[144]

And in April 1918:

Sent circular to all bases stating that leave is at present suspended and nursing sisters detailed to accompany invalids to England must return immediately on completion of this duty unless special leave has been sanctioned by the A.A.G.[145]

Women reacted in different ways to these privations of war, with some seeming content to go without while others found the enforced separation difficult and the unremitting pressures of work hard to tolerate. Many regulations were put in place which were intended to protect nurses while travelling and keep them safe in the eyes of their superiors. On the whole this meant separating them from any men they might encounter ‘en route’ especially rank and file soldiers travelling joyfully and rowdily home. In her war diary, the Matron-in-Chief comments on 13th July 1915:

'All nurses proceeding on leave to travel by the packet, and return by the morning boat, and not travel by either the midnight boat or train, by which officers and men travel when going on leave ...' and a week later that ‘all nurses returning to the front to travel by the 4.27 train and not the midnight one'.[146]

In December 1916 an order was issued stating that ‘nurses must either travel by the leave train or else pay their own fare on the passenger train,’ but this was quickly over-ruled:

The matter is being rectified, at once, as the order was a mistake, and was not intended to include nursing staff, as the leave trains are entirely unsuitable for ladies to travel by, owing to the large numbers travelling and the time the journey takes, and there are no conveniences of any kind for ladies.[147]

Unfortunately the entry doesn’t specify what differences in ‘conveniences’ there were between the leave and passenger trains.

The majority of nurses going on leave travelled from Boulogne to Folkestone. Those employed in hospitals in Le Havre, Étretat and Trouville could on some occasions embark at the port of Le Havre for Southampton, but there were long periods when the port was not permitted for nurses’ leave which then entailed a lengthy rail journey north to Boulogne and an overnight stay before crossing the Channel. If travellers had an additional journey from a Casualty Clearing Station nearer the front it could make an arduous and uncomfortable trip with few opportunities for food, drink or sleep. However, there were some women who attempted to turn these difficulties of travel to their advantage. At the end of December 1916, the Director of Medical Services with the 1st Army complained to the Matron-in-Chief about nursing sisters overstaying their leave:

D.M.S., 1st Army, telephoned, complaining that the Sisters, when on leave, on many occasions failed to return on the day they were expected, which entirely upset the arrangements made for their comfort and convenience – such as having an ambulance to meet them and drive them to their unit, instead of having to travel by a crowded leave train, or by passenger train in the early hours of the morning. This irregularity is causing much inconvenience and if it continues, he will not be able to allow members of the nursing staff to go on 9 days’ leave every three months, and will revert to the same system as on the L of C – 14 days’ every 6 months, if they can get it. He also approved my suggestion that those who could not return up to time should be moved to the Base.[148]

A few days later and armed with a list of names provided by the Director of Medical Services, Miss McCarthy visited the units to interview the women concerned. At the 1/2 London Casualty Clearing Station, Merville, she:

… interviewed one of the sisters who had overstayed her leave and pointed out to her that the excuse she gave was not satisfactory, and told her she would be getting her orders to go to the base, also told her how annoyed the D.M.S. was, as he had arranged matters in such a way to have a car waiting to meet the sisters and drive them back.[149]

The apparent harshness of these actions were typical of Miss McCarthy who believed that the Casualty Clearing Stations deserved staff with a high sense of responsibility. She tried to be even-handed but wanted them staffed exclusively by ‘seriously-minded people.’[150] Her sole intent was to provide sick and wounded soldiers with the best and most experienced staff.

One ongoing problem that the Matron-in-Chief faced was the large number of requests made by members of the Australian and Canadian nursing services to take their leave in places not approved by the War Office. From the start of the war nursing staff were only allowed to take leave in the UK, or if remaining in France, at appointed nurses’ rest and convalescent centres. These were opened both in the immediate vicinity of the Base hospitals and also in the South of France at Cannes and Cap Martin. Nursing Sisters whose homes were in Canada or Australia often had no friends or relatives in the United Kingdom and many made requests to go to Paris, Switzerland, Italy and Ireland, appeals that were almost always refused during the first half of the war.

Large houses were offered by philanthropic ladies and their husbands to serve as nurses’ rest homes. Her Royal Highness Princess Louise, Duchess of Argyll, offered her villa for the purpose, situated in the forest at Hardelot, twelve miles from Boulogne. Later, Captain and Mrs. Warre put their French home, Villa Roquebrune at Cap Martin, at the disposal of the military nursing services each winter, and the house together with the Hotel de l’Esterel at Cannes provided a haven for rest and change in the South of France for hundreds of women.[151]

Many Australians and Canadians still wanted to get right away from the watchfulness and discipline of military life even at its most relaxed and continued to lobby to be allowed to go to Paris, perhaps their only chance of ever visiting the city. At the end of 1917 a house was opened at 175 Faubourg Poissonnière, Paris, as part of the chain of nurses’ rest clubs run under the patronage of Her Royal Highness Princess Victoria. This provided an official leave club for nurses wishing to spend time in the city but with an insistence on strict house rules and regulations, including the need to wear military uniform at all times.[152]

‘Special Leave’ could be granted to women who needed to return home urgently for any one of a variety of reasons, some more urgent than others. Very often these requests were made on account of the death or serious illness of a parent or other close relative and it was usual for at least two weeks’ leave to be allowed in addition to the usual yearly quota. Ordinary leave could also be lengthened by granting an ‘extension’ for a further week or two. The authorities understood that to refuse a request was likely to result in resignation but by mid-1918 the numbers reached such heights that action was taken to restrict them. Women taking their leave in the United Kingdom increasingly applied for extensions due to reasons that could not easily be confirmed Because of this it was decided that due to extreme staff shortages more care needed to be taken to ensure that the reasons were genuine. On 29 October 1918 Miss McCarthy wrote in her diary:

In reply to War Office Letter requesting that specific instances be furnished when extensions of leave have been granted to the Nursing Service on trivial grounds, stated when the request was put forward from this Office, it was not in any way intended to infer that the War Office did not carefully investigate each case, but as extensions of leave were getting numerous, and the shortage of nurses was acutely felt, it was considered advisable to represent this question: that no such cases as were referred to had been furnished to this office in writing, but it is known that it has been frequently said by nurses that they intend to apply for extension of leave when in England. There is a growing tendency among the Nursing Staff to desire long leave, and there is a general feeling that it can be easily obtained.[153]

This resulted in women requesting an extension of leave while at home being required to submit a medical certificate to support their claim, not only for themselves but also for any relative or friend on whose account they might be delayed. For many women the cumulative effect of long hours and arduous duties over several years was beginning to take its toll. While they had no wish to resign, they felt desperately in need of a break of several weeks or months without the pressures of work weighing heavily, both physically and mentally. The cumulative effect of the lack of opportunity for annual leave to be taken was such that by the beginning of November 1918, there were 609 trained nurses and 329 untrained VADs waiting for a chance to fit in their overdue leave. If the Armistice had not been signed in November 1918, the already struggling ranks of military nurses would undoubtedly have begun to suffer even more, but in the event that never had to be put to the test.

*****

[142] Although the term ‘financial year’ may seem out of place in this respect, it is included in the original wording of the Regulations for Admission to Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service

[143] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3989, 18 June 1916

[144] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3989, 26 July 1917, prior to the Third Battle of Ypres

[145] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3990, 12 April 1918, during the German Spring Offensive

[146] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3988

[147] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3989, 17 December 1916

[148] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3989, 30 December 1916

[149] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3989, 3 January 1917

[150] Ibid.

[151] For an account of Convalescent and Rest Homes for Nurses see http://www.scarletfinders.co.uk/15.html, transcribed from WO222/2134

[152] The National Archives, WO222/2134, Report on Convalescent Homes for Nursing Staff in France

[153] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3991, 29 October 1918