THE FAIREST FORCE

9. POSTINGS AND TRANSFERS

*****

On arrival in France for the first time nurses had little idea as to where they would be working. A few women with specialist training might hope for a posting that made use of their particular skills, but keeping each hospital adequately staffed to meet the prevailing military situatioin was always of primary importance and took precedence over individual wants and wishes. Matron-in-Chief Maud McCarthy was exceptionally skilled in examining each batch of newly arrived nurses and placing them where the need was greatest. It might not always please the newcomers but most of them understood that moves from place to place were frequent and they were unlikely to stay anywhere for very long. It was the type of life that needed flexibility on the part of the nursing sisters and one that many had not experienced before.

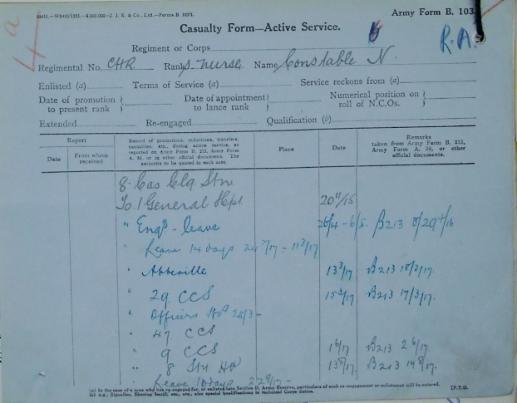

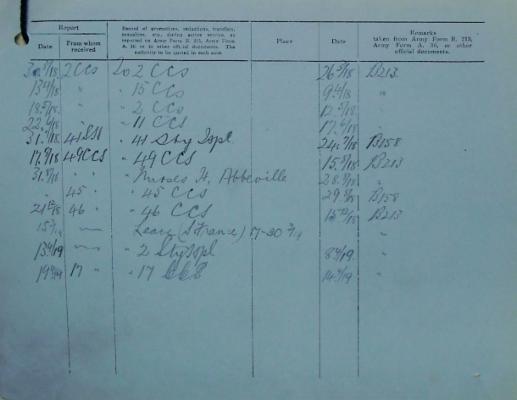

Except in extreme circumstances nurses, however experienced, were required to spend some time in a base hospital before being offered a post at a Casualty Clearing Station, Field Ambulance, or on board a Hospital Train. It was seen as a probationary period and Miss McCarthy thought it vital in order to assess the capabilities of each woman and her suitability for future postings.[99] The National Archives holds service records for 15,792 women who served with the British military nursing services during the Great War and many of the files contain Army Form B.103 ‘Casualty Form – Active Service’ which outlines the various postings and periods of sickness and leave for each woman who served overseas.[100] In the case of nurses, AFB.103 was rarely used before mid-1915 and therefore it’s often impossible to find a full list of postings for women who were in France prior to that date. The surviving forms show that while some women spent the majority of their service at one or two base hospitals, others served in many different units.

As an example, Nora Constable arrived in France on December 9th 1914, as a member of the Civil Hospital Reserve (St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, London). Between that date and her departure from France in April 1919, she worked at one base hospital, four stationary hospitals, an officers’ hospital and a total of eleven different casualty clearing stations.[101]

Army Form B.103 for Nora Constable - even this doesn't include most of her first year [The National Archives, WO399/1684]

Kathleen Flower, QAIMNS Reserve, while Matron at the Sick Sisters' Hospital, Wimereux [IWM Q8005]

Letter received from Matron, 35 General Hospital, saying she had seen the sisters on 31 Ambulance Train who complained that they were ignored and not well treated by the Medical Officers. She had arranged to take these sisters off and replace them but before these ladies were able to be replaced, the train left.[103]

Ambulance Train loading at Doullens [IWM Q8752]

Nurses who had the temperament and skill to cope with the conditions, the work and the foibles of the medical staff were in great demand for train duty and likely to spend more time on trains and less in hospital. In similar manner, some nursing sisters were eminently suited for work on hospital ships. The work on board was considered slightly less arduous than in the base hospitals but many women found that it was not the work that proved their downfall. Miss McCarthy noted on 3 June 1915:

Many nurses … had joined the Netheravon. One of the staff along side had been sea-sick before even starting so replaced her. [This ship is thought to be the ‘Newhaven’].

And on the 14th July, ‘2 nurses from Newhaven had to be replaced as they also were bad sailors, this being the second relief sent’ and on the 14th April 1916, ‘Application from Marseilles for S.N. Mackinnonn Glengorm Castle to be moved from Ship duty in consequence of sleeplessness.’

Requests from nurses for transfers were judged on their merits. Appeals to be relocated nearer friends or to warmer climates such as Egypt were rarely granted unless it was advantageous to the smooth running of the service itself. However, if a nurse at a casualty clearing station found life too stressful with the risk of shelling ever present, a place would quickly be found for her at a base hospital. On the 21st October 1917 four nursing sisters were returned to a base town at their own request, distressed at the death of Nursing Sister Elise Kemp the previous day from injuries received when No.37 CCS was bombed:

Went on to Godwaersvelde to 37 C.C.S. where I saw the O.C. and learnt the particulars of the very trying incident of the night before. Fortunately they had just evacuated and they had only 30 patients in hospital, or the casualties would have been very great. There had been no warning at all beforehand and the bombs landed close to a marqee where the sister, 3 orderlies and 3 patients were killed and others were wounded, two of whom lost their arms. In another marquee the Sister in charge, Miss Devenish Meares, received multiple wounds, fortunately of a not very serious nature. She had an anaesthetic during the night and pieces of shell were removed from her thigh, ankle and fore-arm, and arrangements were being made to send her to the Sick Sisters’ Hospital, St. Omer. I visited her and found her wonderfully plucky. Arranged for Miss Luard, Q.A.I.M.N.S.R., who was waiting at the Nurses’ Home, Abbeville, to join 37 C.C.S. as Sister in charge as soon as possible. Arranged for 4 of the nurses who were very upset to be sent down to the Base.[104]

When the bases themselves became targets in 1917 and 1918, nurses were offered moves back to the United Kingdom or to Marseilles though few chose to accept.

In March 1917, the parents of one VAD, Miss Tod, wrote to the War Office complaining that their daughter was required to work in an Isolation Hospital and they felt the risks to her of contracting an infectious disease made the move unacceptable. Miss Tod was quickly transferred to a Stationary Hospital and the Director-General of Medical Services, Sir Arthur Sloggett, asked that consideration should be given to any VAD who wished not to be employed in this type of hospital. Most of the staff nursing men suffering from infectious diseases found the work interesting but anyone expressing nervousness was moved.[105]

Matron Amelia Ayre with a VAD and medical staff at Calais Isolation Hospital (35 General) 1919

Members of Voluntary Aid Detachments, originally intended to staff hospitals in the United Kingdom under the control of the Joint War Committee, first went to France to augment the staff of military hospitals under War Office control in April 1915.[106] VADs arriving in France already had a number of months’ work experience in the care of military patients, either in a British military hospital or an auxiliary hospital run under the auspices of the British Red Cross Society or Order of St. John. Initial plans were for them to work at the Base Hospitals on the French coast where they could augment the trained staff as did probationers in a civil hospital. This would release more trained nurses for work in forward units such as casualty clearing stations where skill and experience were at a premium.

As the shortage of trained nurses worsened in 1916, the War Office advised that suitable VADs should be placed in casualty clearing stations where work could be found for them.[107] There was a fairly limitless number at that time and it seemed a simple solution. Maud McCarthy, the Matron-in-Chief, felt strongly that the skill mix in CCSs should never be diluted. The number of staff at each was small and in view of the serious nature of the work every one of members had to be capable of doing the work of any other. If VADs were included, although they could be kept busy they could never take the place of a fully-trained nurse in areas such as administration, the operating theatre or more complicated ward work. She felt that having VADs in these units would be equal at busy times to carrying stragglers. Sir Arthur Sloggett, the Director-General of Medical Services in France and Flanders, continued to support the idea but after a visit to London in November 1916 to discuss the matter with her colleagues, Miss McCarthy had serious words with him:

Told him of my recent visit to London and the general feeling in the nursing world against V.A.D.’s being sent into front areas for duty. I had told him I had seen many civil matrons on the subject and they had all expressed surprise at the decision, and felt certain that if the suggestion was carried out, a large number of trained nurses would send in their resignations at once. I told him also that the Dowager Countess Roberts and Countess Airlie who are on the Q.A.I.M.N.S. Nursing Board expressed themselves very strongly on the subject. The D.G.M.S. said that while we had the nurses of a suitable character, to carry on as we were doing, but he emphasized the fact that it was important to make the best use of the material we had in the country, and he left it to me to do the best I could. He pointed out that although V.A.D.’s were not fully trained, they had proved themselves to be very capable and efficient workers.[108]

The discussions rumbled on well into 1918 and as the lack of trained staff became even more acute Miss McCarthy remained firm in her determination to cope without resorting to the use of VADs in casualty clearing stations. She did relent, however, on employing them in Stationary Hospitals and in July 1917 the first VADs were posted to No.6 and No.12 Stationary Hospitals, situated at Frevent and St. Pol respectively.[109] Sir Arthur Lawley, the British Red Cross Society’s Commissioner in France felt that VADs had been under-used in France:

… he felt that the best had not been done for the V.A.D. with regard to their training. I pointed out that the V.A.D. had come out as a V.A.D., that those who wished to be properly trained should have gone to a Civil Hospital for that purpose, that at a time like this it was impossible to attempt, or for anyone to ever think that the training of V.A.D.’s as Nurses could be undertaken, that I fully appreciated the value and worth of the V.A.D.’s but that it must never be forgotten that they have most wonderful opportunities of gaining practical experience, and have had ever since they came out to France, through working under the very finest surgeons and consultants in the world, and with the most highly trained women, but that naturally if they wish to be certificated Nurses they will require a little more that the practical experience they have gained while on Active Service, and which had been such an enormous help in assisting in the nursing and care of the sick and wounded.[110]

While VADs were likely to spend long periods of time at one hospital, most of those who worked for several years in France experienced at least two or three separate units and had the chance to gain experience in different medical and surgical areas. For the trained staff, my perception, based on observation and service records rather than proof, is that nurses who had many moves around forward units – casualty clearing stations, field ambulances and ambulance trains – were often the most experienced, able and successful of wartime nurses.

*****

[97] The National Archives, WO222/2134, ‘Embarkation.’

[98] The National Archives, WO222/2134, ‘Embarkation.’

[99] The National Archives, WO222/2134, ‘Casualty Clearing Stations’, available in transcription on Scarletfinders website

[100] The National Archives, WO399, Nursing Service Records, First World War

[101] The National Archives, WO399/1684, service file of Nora Constable

[102] The National Archives, WO399/2796, service file of Kathleen Flower

[103] The National Archives, WO95/3989, War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief with the B.E.F. in France and Flanders

[104] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3990

[105] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3989, 1 April, 1917

[106] Army Council Instruction 101, March 1915

[107] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3989, 4 November 1916

[108] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3989, 30 November 1916. It must be noted here that Sir Arthur Sloggett had a daughter, Dorothy, working in France as a VAD, and he had personal reasons for so strongly putting their case.

[109] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3989, 17 July 1917

[110 ] War Diary of the Matron-in-Chief, The National Archives, WO95/3991, 26 October 1918